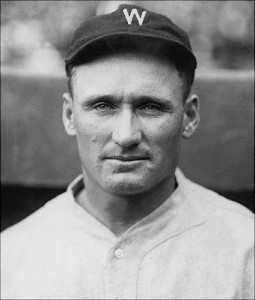

Walter “Big Train” Johnson in the Improvement Era

Walter “Big Train” Johnson in the Improvement Era

If Mariano Rivera wrote an article for the Ensign, would you be surprised? Would you read the article?

If Mariano Rivera wrote an article for the Ensign, would you be surprised? Would you read the article?

The idea seems crazy—the Ensign doesn’t publish articles like that, does it? I suppose not. But its predecessor, the Improvement Era, published from 1897 to 1970, did publish articles by non-Mormons occasionally, and those articles even included some without a religious message.

And for baseball fans, he best of these articles might be the following article by Walter “Big Train” Johnson, published just two years before he was inducted into the inaugural class of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

.

Because Walter Johnson is among the two or three greatest heroes of baseball and because he once played baseball in our own territory—Weiser, Idaho—he was asked to write an article especially for “The Improvement Era” telling of his biggest thrill. Read this article and you will know that in Johnson’s case, as in so many others, humility accompanies greatness.

.

My Biggest Thrill in Baseball

by Walter Johnson

Known everywhere as “Big Train,” former pitcher for the Washington, D. C., Senators, now manager of the Cleveland Indians

WHEN a fellow has had a whole lot of something at one time or another, it is a little hard to figure out which he considers the best. And so it is with baseball thrills. I’ve often been asked what I considered my biggest and, until the Fall of 1924, I really did not know.

I started with the Washington Club back in August, 1907, and got my first thrill when called on in a relief role for my major league debut. From then on, they came rather frequently. In mentioning some, I hope I will not appear to be boasting. The fact of the matter is that I had, I believe, one of the most wonderful arms in the world, so that any little success I have had in a baseball way has been due to that God-given gift, rather than to any particular amount of ability.

My baseball life has been an almost perfect one. Three times, I thought I was enjoying my biggest thrill when Washington fans had days in my honor, gave me presents and made me think I was the greatest fellow in the world. In 1920, I was fortunate enough to pitch a no-hit, no-run game against the Boston Red Sox and, here, too, I surely got a thrill.

My heart came up in my throat and I came near crying in the 1924 season when I was voted the most valuable player to my team in the American League and again in 1927 when, as part of a celebration of my 20th anniversary with the Washington Club, the League presented me with the first “distinguished service medal” it had ever given.

I SEE by the record books, I am credited with a lot of high marks, such as 3,497 strikeouts, best earned run average for six different years, led the league in most games won six times, had a string of 16 consecutive victories, pitched 56 scoreless innings in a row, won 28 games, or more in three successive seasons, hold the shutout game record, and led the league in strikeouts for 12 years.

Naturally in making these records, I had my share of thrills but, as I said before, the “daddy of ’em all” came in 1924—in the seventh and deciding game of the world series against the New York Giants of the National League.

I had quite a thrill during the season in winning 20 games to help the Washington Club win its first American League pennant after years and years of trying. And the thought of finally getting into a world series after having been on a losing team for 17 years also gave me quite a kick.

But it was in the seventh game that I got what the cartoonist calls “The thrill that comes once in a lifetime.” Just picture the setting in which I suddenly found myself. I had pitched the first game and lost it, 4-3, after 11 thrilling innings. With the teams tied, I got another chance in the fifth game and was beaten again, allowing the Giants five runs in the last few innings.

Tom Zachary won his third game of the series to put the Washington Club even at three games apiece and you can imagine how I felt being charged with two of the defeats and not even looking good in the fifth game.

I guess I must have looked mighty dejected sitting on the bench and in the locker room afterwards, for that night I was sitting home feeling mighty blue when Manager Bucky Harris called me on the phone.

“Don’t worry,” he said, “I’ve still got confidence in you and might need you in tomorrow’s game. Go to bed early and be ready because, if I need you, I will need you badly.”

This cheered me up considerably but I still felt that I had had my opportunity and “booted” it, as the players say. But the world’s championship and considerable cash were at stake and, while I wasn’t particularly optimistic, I got a good night’s rest and actually prayed that I would get this chance to redeem myself.

I got it in the ninth inning with the score tied at 3-3. I had my troubles but also had some good luck and managed to hold the Giants in check. We scored a run in the twelfth, McNeely’s famous bounder over Lindstrom’s head—driving it in, after we had had two wonderful breaks of luck. First Catcher Gowdy had fallen over his mask, which caused him to miss an easy pop-foul off Muddy Ruel’s bat and gave Ruel a chance to double and a minute or so later Jackson, Giant shortstop, fumbled my grounder.

When Ruel trotted home with the run that gave us the game and Washington its only world series—and gave me credit for the victory—that was the thrill which I will always remember as easily my greatest in more than 20 years of baseball play.

Who is Walter Johnson and Why?

WALTER JOHNSON was born at Humboldt, Kansas, Nov. 6, 1887. Started in baseball as pitcher for Fullerton High School team, California. Got his first pro contract with Tacoma of North-western League in 1906 at 18. Subsequently joined the Weiser, Idaho, semipros, and did considerable pitching in that section of the country for town and sectional teams at so much per game.

Joe Cantillon was managing the Washington Club and some friend in the vicinity of Weiser continually wrote urging that he sign Johnson. Catcher Cliff Blankenship was in jured at the time and Cantillon finally decided to “shut up” his friend by having Blankenship take a look at this great phenom, having little confidence that Blankenship would recommend signing him.

Johnson, himself, evidently did not rate himself so highly for, before agreeing to come to Washington for a tryout, he insisted he be given not only a railroad ticket to Washington but also expenses back to Weiser. Johnson pitched his first major league game here on Aug. 2, 1907—at age of 19—and was beaten by the Detroit Tigers, 3-2. But he showed plenty of stuff, confining Cobb, Crawford, Rossman and the other Tiger sluggers to six hits in eight rounds.

Johnson seemed to have nothing but a fast ball and Cantillon informed him that he had to have more than that to get by in the big leagues and had Johnson experimenting with the “spitball” for a while. But Johnson started winning games, throwing the ball past the batters before they could get their bats off their shoulders and, because of this great speed, he was dubbed the “Big Train.”

The end of Johnson’s mound career was hastened by a blow on the left leg, which fractured the member, while at the Spring training camp at Tampa, Fla., in 1927, a drive from Joe Judge’s bat doing the damage. He was given his unconditional release—quite an expensive present by President Clark Griffith, of the Washington Club—so that he could manage the Newark Internationals in 1928 and he returned to the Capital City in 1929 to pilot the Nats, serving four seasons. Last June, he was signed to manage the Cleveland Indians.

—Frank H. Young, “Washington Post Sports.”

Improvement Era, v37 n6

June 1934

.

The careful reader will note that nothing in the above article is specific to Mormonism or to Utah, which would lead me to believe that this is likely an article written for publication elsewhere, except for the head note that says the Improvement Era solicited the article. Even so, it is possible that Johnson simply provided an article he had provided previously to others. I also don’t think that we should necessarily believe that it was written by Johnson himself — or at least not by him alone. Likely Johnson had a journalist “ghostwrite” this article.

Still, what is most interesting for us today is that it was solicited by and appeared in a Mormon religious periodical alongside inspirational and doctrinal articles by General Authorities and other members.

Should it have? Would you have included it if you were the editor of the Improvement Era in 1934? Do you think we should ask for the Ensign to include articles like this today?

I like this. In “the olden days,” when the MIA (sponsor of the Era) was the recreation arm of the Church, it would make perfect sense to find a positive article by a sports figure, I suppose. They seem to have published a lot of things that weren’t strictly religious but were for “mutual improvement.” Anyway, this was a cool find.

Today, such a thing would certainly feel out of place, wouldn’t it?